Pro-Con: New year brings changes to grading scale

Nov 17, 2017

Pro: Keep giving students another try

Two years ago, the grading system had been reviewed and revised with many new edits. Some of those changes allow assignments to be turned in at any time; tests could be retaken at the teachers discretion. One of the bigger changes is the summative and formative assessment rubric.

This past summer, the grading system was once again revised to change points in the rules to help improve student productivity.

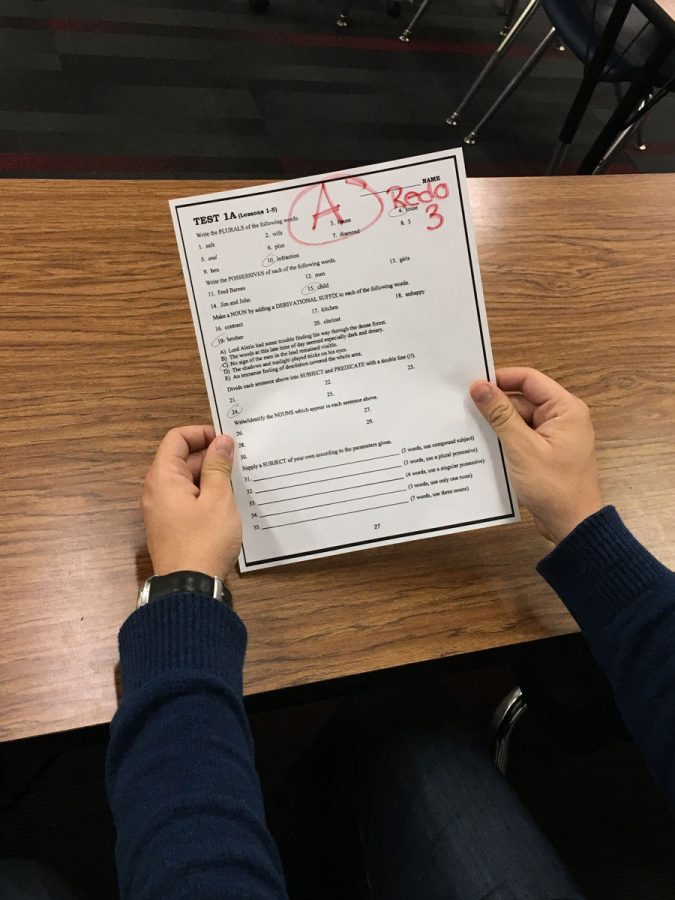

One of the new points is that students can no longer receive a higher score than 93 percent on retakes.

Overall, this is a good policy. It will help inspire students to study instead of failing a test just to retake it and get 100 percent.

Last year some students would purposely flunk tests to have the opportunity to look at them and have a better chance when they retake it.

The new set up discourages students from not doing work or not paying attention.

Another way the new setup will improve productivity is that late assignments now have a deadline. This pushes students to get their work done before hand and on time, thus improving grades.

Even though some changes are good, others are more difficult to understand.

One of the new problems is the limit of one retake on a test or quiz. If someone was really trying hard to succeed, but did not understand the content, they should have more than one retake opportunity.

If students meet certain criteria, they should be allowed more retakes. For example, if the student has taken time to discuss materials with the teacher, this should be worthy of a retake.

If they were to meet the requirements, they should be allowed more trys.

Overall, there may still be difficulties due to the new grading system, but it is going to help raise productivity and success in students.

Con: Setting unrealistic expectations

Con: Setting unrealistic expectations

In 2016, a new grading policy was implemented to help students grades be based on what is learned instead of what is completed. This included having no penalty for formative late work and unlimited retakes on assessments for full credit.

It has been a year since this policy was put into place, and a few changes have been added to kick off the new school year.

Now students have two days to redo formative late work. For summative late work, the teacher decides the time in which the students will have to redo a summative assessment. These can only be redone up to 93 percent.

Although these new changes are an improvement from last year, they are still not realistic to say the least. The policy is more strict, but it does not address the biggest issue, reality. It is not preparing students for the real world.

When students move past high school and into the a competitive world, whether it be college or the work force, everything is going to be completely different. There are no redo’s in college or at a real job – people are expected to complete their work in with no excuses. When something is done wrong, there is rarely a chance to fix it or turn it in for a better result.

People are held to the expectation that they will learn from their mistakes and do things right the first time.

The grading scale that is currently in place encourages students to be lazy since they will still have a chance to do it later and still get an A.

The only actual benefit from the grading policy is the concept of summative and formative assignment. The summative assignments, tests, quizzes, and large assessments, are worth 80 percent of the student’s overall grade and the formative assignments, practice quizzes and smaller assignments, being worth 20 percent.

This makes it so students grades are based off of what they know instead of what they have filled out. Students can no longer cheat, bomb the tests and still have a good grade from all of the buffer assignments.

Even with this positive, the grading policy that is in tact still negatively impacts student’s futures by leaving them unprepared for what the future holds. The policy misleads teenagers into thinking life is different than what it truly holds.